THE HAMSTERLEY HALL SILVERED MIRROR

W: 43.5” / 110cm

Further images

Provenance

Standish Robert Gage Prendergast Vereker, 7th Viscount Gort, MC, KStJ (1888-1975), Hamsterley Hall, County Durham, England

By descent to his grandnice the Hon. Catherine Mary Wass, OBE (1942-2021)

Private Collection: California, USA

Literature

Bowett, A., English Furniture: 1660-1714 (Woodbridge: 2002), pp. 12-5, 126-7, 139-43

Colville, J. R., Man of Valour: The Life of Field-Marshal the Viscount Gort (London, 1972)

Thornton, P., Seventeenth-Century Interior Decoration in England, France and Holland (New Haven and London, 1978), pp. 232-3, pl. 218

C. Hussey, ‘Hamsterley Hall, Durham: The Seat of the Hon. S. R. Vereker, M. C.’, Country Life, 21st October 1939, pp. 418-22

COMPARE

Example in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London (Accession No. W.37-1949)

Example exhibited at The Grosvenor House Art & Antiques Fair, 1996 (Catalogue, p. 106)

Silver metal examples at Knole, Kent (NT 130034 and NT 130014.1/NT 130014.2, including silver metal furniture NT 130035 and NT 130036.1/NT 130036.2)

Silver metal examples in the Royal Collection (RCIN 35300, RCIN 35392 and RCIN 35302, including silver metal furniture RCIN 35299 and RCIN 35298)

Child, Graham, World Mirrors 1650-1900 (London, 1990), pp. 62-3

Hinkley, F. Lewis, Queen Anne & Georgian Looking Glasses (London, 1987), p. 87, pl. 61

Schiffer, Herbert F., The Mirror Book (New York, 1983), pp. 36-42

Wills, Geoffrey, English Looking Glasses (1670-1820) (London, 1965), p. 65, fig. 1; p. 67, figs. 7-8

Mirrors of this type, boldly modelled in high relief and silvered, and monumental in scale, are exceedingly scarce. Among the few other examples is the mirror bearing the arms of Gough of Old Fallings Hall, Staffordshire, for Sir Henry Gough (1649-1724) in the Victoria & Albert Museum and another incorporating the arms of Fisher of Packington, Warwickshire, in the Lady Lever Art Gallery, Liverpool.1

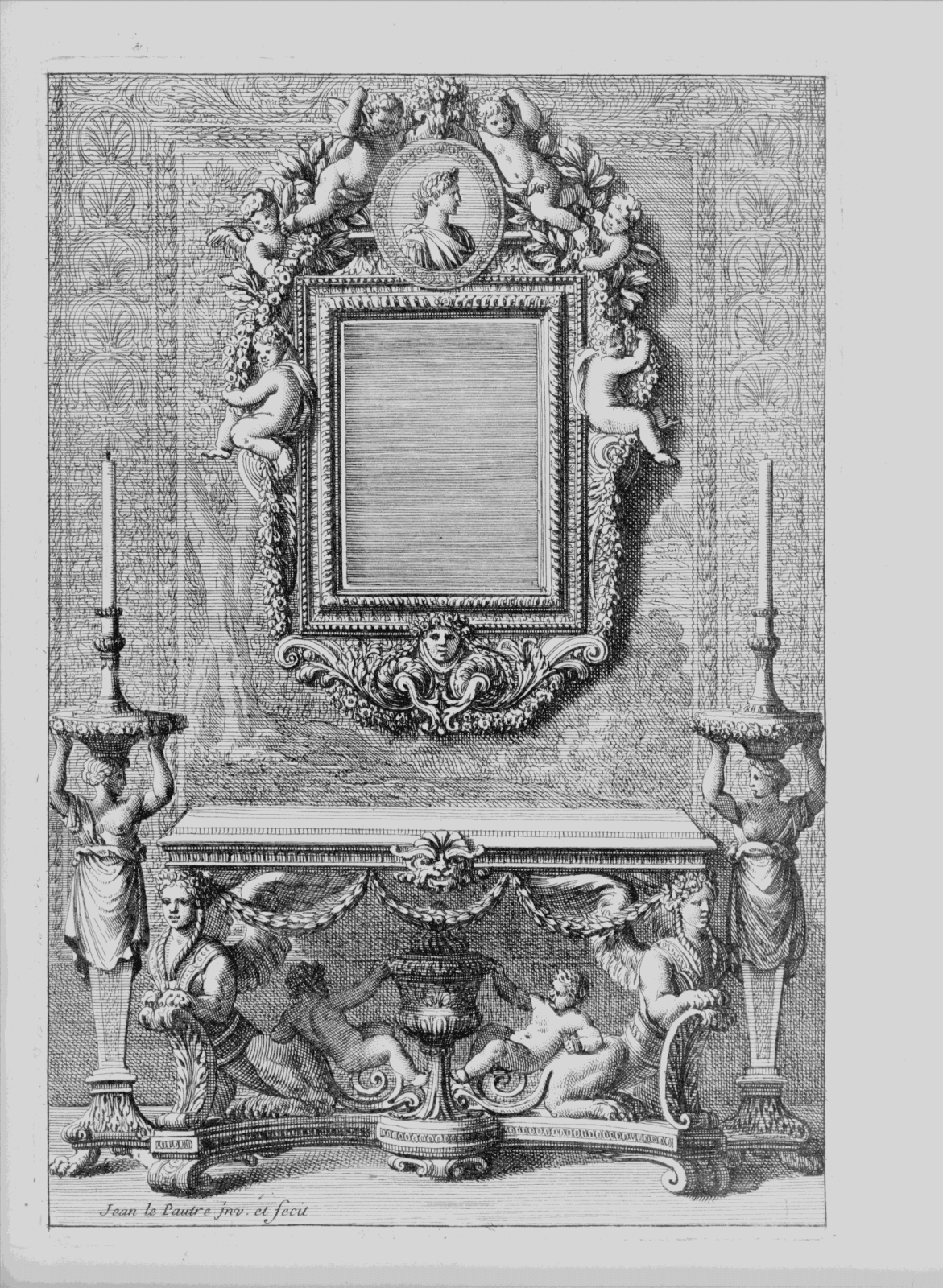

Silvering would have given the mirror the appearance of solid silver, associating it with contemporary mirrors executed in the metal, such as those at Knole, Kent and in the Royal Collection, each supplied with a table and stands en suite to form a triad.2 Carved with putti the present mirror derives from French baroque designs of the second half of the seventeenth century, exemplified by a Parisian engraving of c. 1670.3 The mirror thus reflects the ‘rampant Francophalia’ that the king’s taste engendered amongst his innermost circle of courtiers, who in turn expressed this most lavishly at their country houses, influencing style across the country.4

In their English context these motifs were perhaps uniquely symbolic. As society salved the scars of Protectorate privations and underwent serious economic recession in the 1660s, which reached their nadir when London endured the Great Plague (1665), the Great Fire (1666) and a second Anglo-Dutch war (1665-67), the mirror would represent the change in the nation’s fortunes that soon followed.5 Economic growth began at the end of the decade, developing into a boom lasting into the 1690s, on the tide of a woollen cloth trade finding markets abroad and a flourishing re-export business. This mirror represents this rejuvenation and prosperity. Berries, branches, flowers and a cornucopia symbolise growth and plenty, while ribbons, swags and putti playing instruments capture the mood and sounds of celebration. The mirror itself is a product of this increasing wealth and a marker of the accelerating pace of concomitant technological advancement, with plate of this size being not just expensive but highly difficult to produce, and previously impossible.

The mirror was in the collection of connoisseur Standish Robert Gage Prendergast Vereker, 7th Viscount Gort, that also included the cabinet-on-stand attributed to André-Charles Boulle (1642-1732), now in the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (77.DA.1).6 Standish housed his collections at Hamsterley Hall, built largely in c. 1770 by Henry Swinburne in eighteenth-century gothic style, with a crenelated roof line, ogival windows and a fanciful bay, but stamped his own mark on the place, adding salvaged Jacobean elements from Beaudesert (recently demolished in 1935 and including a cupola to serve as a summer house), an early eighteenth-century baroque doorcase and shell canopy and a Gothic pinnacle, removed from the earlier Houses of Parliament during restoration works.7

The mirror was a fitting part of his collection. A celebration of Restoration England - even carved with a sunflower, the symbol of monarchical loyalty famously deployed by Van Dyck - the mirror reflects the same service to crown and country shown by his family for centuries, beginning with his ancestor and contemporary of the mirror, John Vereker, who was one of the gallant gentlemen, afterwards styled ‘the 49 officers’, deprived of his commission by Cromwell for their royalist sentiments, but rewarded with lands by the new king, Charles II, for his loyalty to the crown.8

His descendant, Charles Vereker (1768-1842), Colonel of the Limerick Militia and later the 2nd Viscount, was renowned for his important victory over the French at Killala Bay, County Sligo in 1798. He inherited the viscounty from his maternal uncle, the heir of the Prendergasts of Tipperary and County Galway, themselves descended from Maurice, Lord of Prendergast in Pembrokeshire, one of the Norman knights who sailed to Ireland with Strongbow in 1179.9 The 5th Viscount, who married a daughter and co-heiress of R. S. Surtees (1805-1864), the famous author who wrote his novels at Hamsterley, was in the Royal Artillery, advancing to captain in the 4th Brigade, South Irish Division. He was the father of Standish and his elder brother John, the 6th Viscount, one of the most decorated soldiers of the Great War, mentioned in dispatches nine times and known to his soldiers as Tiger Gort.

He received the Victoria Cross in September 1918 for his actions at Canal du Nord, the official citation noting his ‘most conspicuous bravery’, ‘devotion to duty’ and ‘utter disregard of personal safety’ in no uncertain terms.10 In 1937, Gort was appointed Chief of the Imperial General Staff and in 1939 named Commander in Chief of the British Expeditionary Force. After action on Malta where he was governor he received his Field Marshal’s baton from King George VI in 1943.11

Standish himself served in the Great War, being wounded three times and earning a Military Cross, and in the Second, under his brother, becoming an honorary colonel in 1948. He and his wife donated generously throughout their lives, giving Bunratty Castle to the Irish people in 1954 and an important collection of Renaissance paintings to the Winnipeg Art Gallery in 1973, also completing restoration of Surtees House in Newcastle. When he died, the mirror passed to his brother’s granddaughter, The Hon. Catherine Mary ‘Kate’ Wass, OBE. Kate was a direct ancestor of George III via his third son Prince William, Duke of Clarence, later William IV, and his mistress, the Drury Lane actress Mrs Jordan (1761-1816), who lived together for twenty years at Bushy House. Kate’s father, William Philip Sidney, 1st Viscount De L’Isle, was himself a war hero himself, receiving the Victoria Cross for his defence at Anzio in 1944.

1 Victoria & Albert Museum, Accession No. W.37-1949; illustrated Schiffer, Herbert F., The Mirror Book (New York, 1983), pp. 40-1, fig. 61, and other examples pp. 36-43

2 For Knole, see National Trust, 130034 & 130014.1/2, and those in the Royal Collection, see RCIN 35300

3 P. Thornton, Seventeenth-Century Interior Decoration (New Haven, 1978), pp. 232-3, pl. 218; c.f. mirror formerly in the Vernon Collection at Sudbury Hall, Derbyshire (NT 652738), and another of highly comparable design, Schiffer (1983), pp. 42-3, fig. 64, though of silver and gold leaf

4 A. Bowett, English Furniture 1660-1714 From Charles II to Queen Anne (Woodbridge, 2002), pp. 17-20

5 Ibid., pp. 26-7; with ‘public matters in a most sad condition’ and ‘all sober men…fearful of the ruin of the whole Kingdom’, on New Year’s Eve in 1666 Samuel Pepys saw no prospect of improvement, beseeching ‘good God deliver us’.

6 C. Hussey, ‘Hamsterley Hall, Durham: The Seat of the Hon. S. R. Vereker, M. C.’, Country Life, 21st October 1939, pp. 418-22

7 ‘Hamsterley Hall - Halls & Manors of County Durham & The Borders’, Sunniside Local History Society, no. 4

8 Brian de Breffny, ‘The Vereker Family’, Irish Ancestor, Vol. V., No. 2 (1973), pp. 69-75

9 Hussey, Country Life (1939), p. 418

10 ‘No. 30466’. The London Gazette (Supplement). 8 January 1918, pp. 557–8

11 c.f. also Colville, J. R., Man of Valour: The Life of Field-Marshal the Viscount Gort (London, 1972)