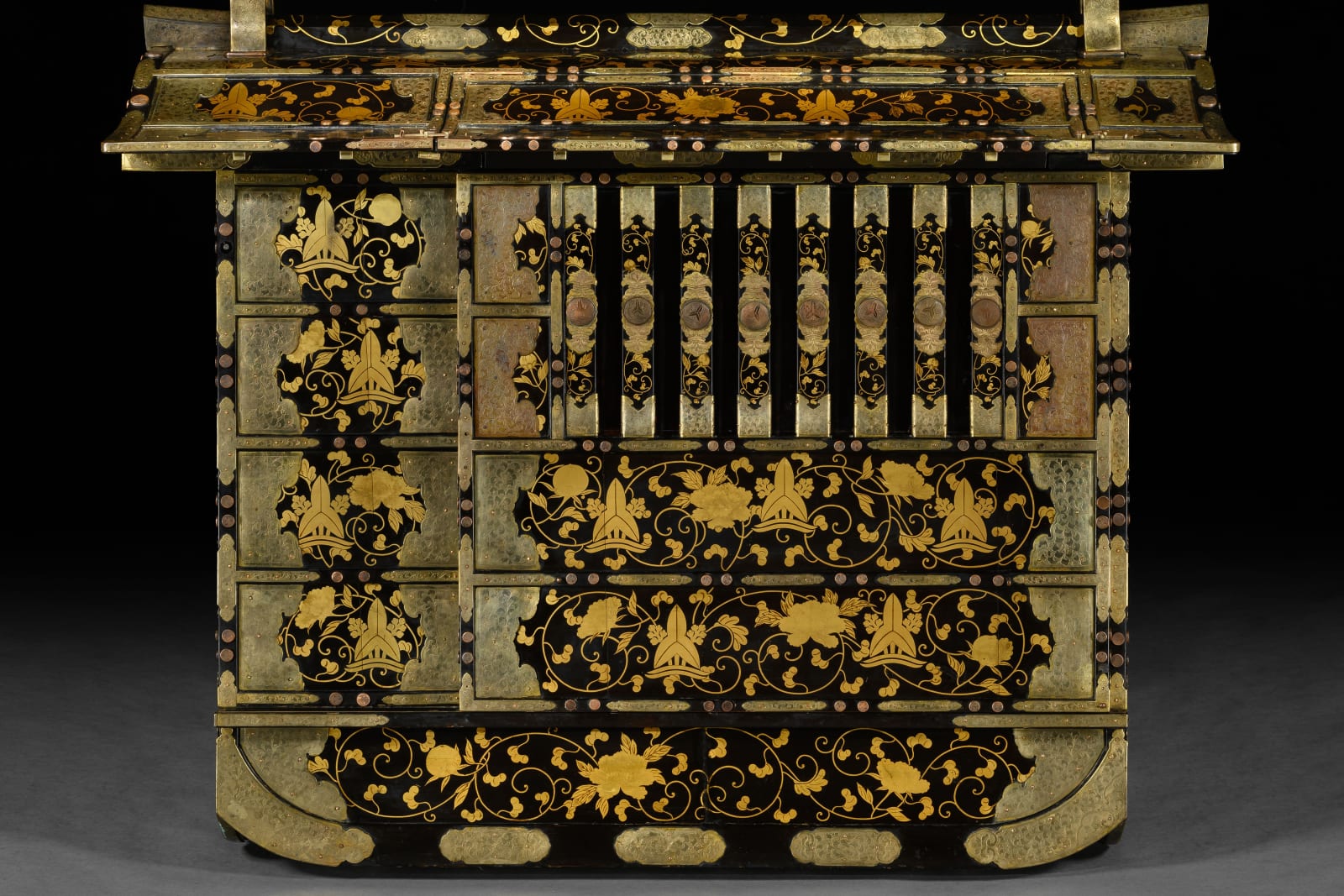

A GILT-COPPER AND GOLD MAKI-E LACQUER PALANQUIN OR NORIMONO

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

Provenance

Made for a member of the Mizuno clan, possibly Mizuno Tadakiyo (1833-1884), daimyō of Yamagata Domain and Rōjū in service to the Tokugawa shogunate, for his marriage in 1857 to a daughter of Inoue Masahari (1805-1847), a fellow Rōjū and daimyō of Tanagura Domain, and head of the Inoue clan

Private Collection: France, Paris

Exhibitions

Victoria & Albert Museum, London, UK (Accession No. 48-1874)

Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Asian Art, Washington, USA, Arthur M. Sackler Collection (Accession No. S1985.1a-h)

Tokyo Fuji Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan (Accession No. 01165)

Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design (Accession No. 2004.113)

Musée national de la voiture, Compiègne, France (CMV 77)

An Edo period, gilt-copper and black and gold maki-e lacquer palanquin, the exterior decorated with peonies, môn and karakusa together with the crest of the Mizuno clan (omodaka (threeleaf arrowhead) with water in a stream below), a prominent samurai family in Japan with significant influence during the Sengoku and Edo periods; the gilt-copper mounts chiselled with similar foliate decoration, the shuttered doors opening to reveal a padded interior, retaining the original embroidered silk upholstery, and painted on paper with flowers, cranes, pines and cherry trees, together with the original carrying beam, similarly lacquered and mounted.

The lacquered surface of this palanquin was crafted using the Japanese maki-e technique, in which fine gold powder is sprinkled onto wet lacquer to create intricate designs. The term maki-e, meaning “sprinkled painting,” perfectly describes the decoration, which features the Mizuno clan crest amid arabesque patterns of peonies, môn, and karakusa (winding plants)—symbols of prosperity and eternity in Japanese culture.

Accentuating its grandeur, the palanquin’s corners, shutters, and rails are adorned with gleaming gilt-copper mounts, skillfully shaped and finely chiseled with sprays of foliage and flowers. The interior is just as exquisite, upholstered with embroidered silk and painted with vibrant outdoor scenes, including cherry blossoms by the water and soaring red-crowned cranes—symbols of good fortune and longevity, making this decoration particularly fitting for a wedding.

High-status palanquins like this, known as norimono, were commissioned to carry the brides of daimyō—the warrior lords of Japan’s feudal class—during their wedding processions. These elaborate events were grand displays of wealth and power, symbolizing the union of prominent families. Brides traveled with an entourage transporting their dowries in lacquered chests that matched the decoration of the norimono, further emphasizing the prestige of the occasion.

This norimono bears the sawa crest of an omodaka (three-leaf arrowhead) with flowing water, represented by two wavy lines, identifying its connection to the Mizuno clan. Dating to the mid-19th century, it was almost certainly commissioned for Mizuno Tadakiyo (1833–1884), head of the family, daimyō of Yamagata Domain, and a senior official in the Tokugawa shogunate. In 1857, he married a daughter of Inoue Masahari (1805–1847), daimyō of Tanagura Domain.

Tadakiyo was a notable figure during Japan’s Bakumatsu period. His father, Mizuno Tadakuni, once held substantial political power under the 12th shogun, Tokugawa Ieyoshi, but fell from favor after the failure of the Tenpō Reforms. Following his father’s retirement and exile, Tadakiyo assumed leadership in 1845. His fortunes revived after his father’s pardon in 1851, and he ascended to significant positions such as Jisha-bugyō (Commissioner of Shrines and Temples) and wakadoshiyori (Junior Councillor). By 1862, he had become a Rōjū (senior advisor), playing a key role in modernizing Japan’s military under Shogun Tokugawa Iemochi.

This wedding palanquin epitomizes the elegant form and lavish ornamentation characteristic of Edo-period norimono for daimyō families. It closely resembles other prestigious examples, such as the norimono in the Smithsonian, commissioned in 1856 for Atsu-hime, wife of the 13th Tokugawa shogun, and the Victoria & Albert Museum’s 1857 example, made for Kiihime, the adopted daughter of the same shogun.

As a rare and culturally significant artifact, this palanquin encapsulates the grandeur of Japan’s Edo period, offering a glimpse into the opulence, traditions, and hierarchical structures of feudal society in its final years.