A PAIR OF CARVED SOAPSTONE FIGURES OF A MANDARIN AND FEMALE ATTENDANT

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 12

)

Provenance

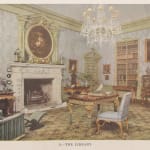

The collection of Mr Basil (1884-1950) and the Hon. Mrs Nellie Ionides (1883-1962), the Library at Buxted Park, Sussex

By descent to Lady Camilla Panufnik, née Jessel, (b.1937), who married renown symphonic composer, Andrzej Panufnik

Literature

F. Gordon Roe, ‘A Chinese Craft: Chinese Soapstone Carvings’, The Connoisseur (London, 1920), pp. 157-61

Publications

R. Soame Jenyns, Chinese Art: Textiles – Glass and Painting of Glass – Carvings in Ivory and Rhinoceros Horn – Carvings in Hardstones – Snuff Bottles – Inkcakes and Inkstones (2nd ed., rev. William Watson) (Oxford, 1981), p. 208, fig. 181

Hussey, Christopher, ‘Buxted Park, Sussex – II, The Home of Mr. and the Hon. Mrs. Basil Ionides’, Country Life (11th August 1950), p. 445, fig. 8, the Library, showing the figures in situ

The extraordinary nature of the present figures is constituted not only by their quality and large size but their subject matter, which is of secular court officials, where the great majority Chinese soapstone figural carvings, distinct from those often of mythological beasts incorporated into seals, depict sacred figures, often Guanyin, an Immortal or a luohan or bodhisattva.

A handful of small soapstone carvings of Western secular figures are known, of which two were also in the Ionides collection.1 Also known are a number of carvings of Chinese scholars and legendary soldiers.2 Yet other examples of court officials, of this quality and scale, do not appear in literature, private or institutional collections or auction data, with the present figures appearing to be unique.

The mandarin and his attendant are superbly modelled. They are sensitively postured in the folds of their flowing robes and their faces are charged with contemplative expression. The figures are of carved soapstone, enriched with veins of colour and polychrome and gold decoration. The male figure wears the rank badge, buzi, of a crane, emblazoned amongst clouds and roundels of flowers and stylised scrolling grasses as a large square on his chest and back, identifying him as a civil official, a mandarin, of the first rank. A square badge symbolised earth while a circular badge, worn by members of the imperial family, represented heaven.3 In the same way, the mandarin's robe is embroidered with four-clawed dragons, a symbol of noble rank below that of an imperial family member permitted to wear the five-clawed dragon. Below these dragons, whose long tails wrap around the leg portion of the robe, are waves which crash against towering rocks rising up amongst clouds.

The female figure, or possibly the mandarin’s wife, as has been suggested by R. Soame Jenyns, wears similarly rich clothing, incised with clouds, stylised embroidery and scalloped roundels of flowers and grasses.4 Married Manchu women would typically hair in the gaoliang way, with a chignon fashioned around a piece of wood positioned horizontally across her head, signifying their married status, instead of a simple chignon, which indicated unmarried status.5 Likewise, Qing edicts outlining female customs for rank badges permitted wives of officials to wear their husband’s insignia, which this figure does not. The relation of the figures is thus difficult to determine, but their stylised nature, not faithful representations of Qing dress and customs, means the possibility of their representing a mandarin and his wife, intended by the artist, remains.

1 For figures of westerners, see David Howard and John Ayers, China for the West, vol. II (London & New York, 1978), pp. 666-7, figs. 689-90

2 For scholars and legendary soldiers see, for e.g., the British Museum (SLMisc.1174)

3 Christie’s, Unmistaken identity: a guide to the rank badges of ancient China (August 2022)

4 R. Soame Jenyns, Chinese Art: Textiles – Glass and Painting of Glass – Carvings in Ivory and Rhinoceros Horn – Carvings in Hardstones – Snuff Bottles – Inkcakes and Inkstones (2nd ed., rev. William Watson) (Oxford, 1981), p. 208, fig. 181

5 Thierry Audric, Chinese Reverse Glass Painting, 1720-1820: An Artistic Meeting Between China and the West (Bern, 2020), p. 56